Table of Contents

ToggleIntroduction to Plato’s Protagoras

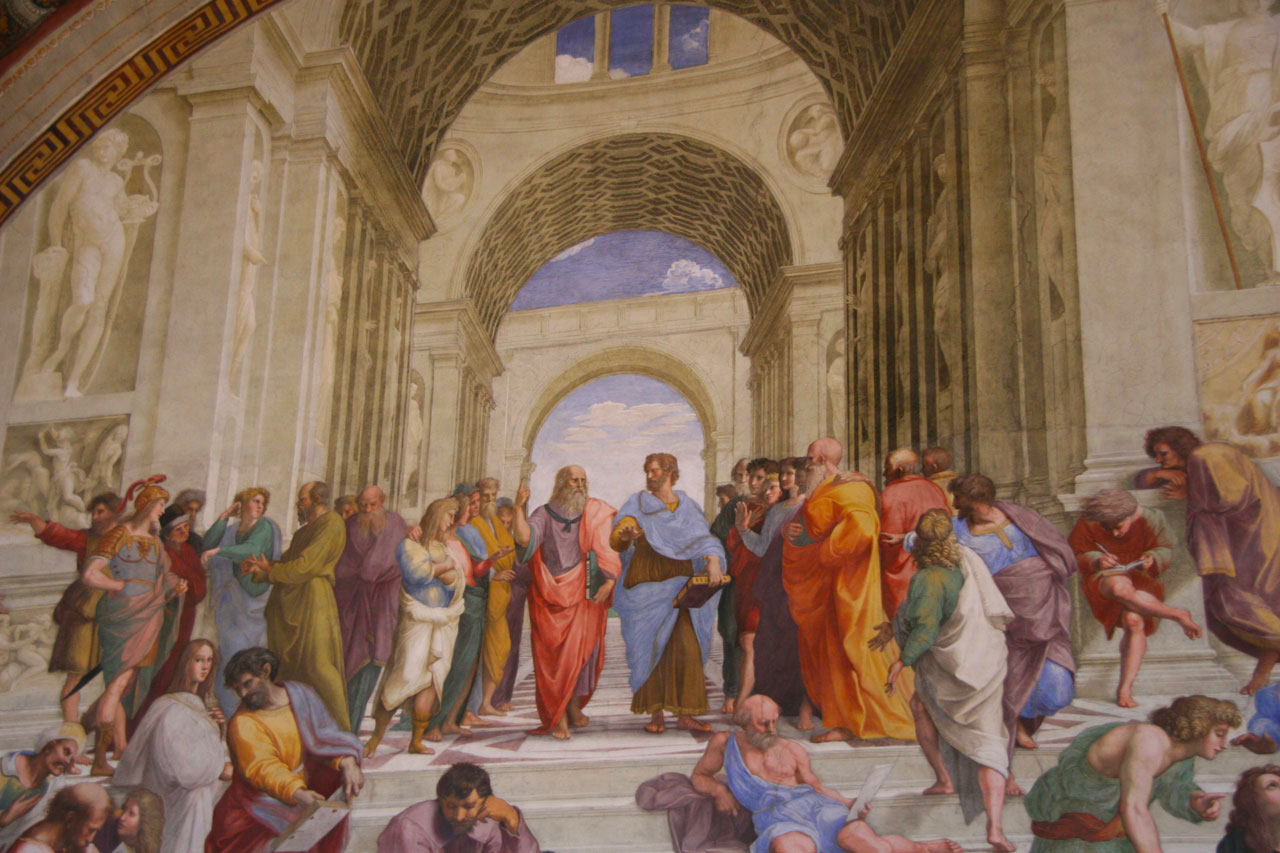

Summary And Themes Of Plato’s Protagoras Plato’s Protagoras is one of the most important dialogues in the history of Western philosophy, exploring themes such as virtue, knowledge, and education. It takes the form of a conversation between Socrates and Protagoras, a famous sophist of the time. The dialogue takes place in a social setting, where Socrates is attending a gathering of wealthy young men and prominent thinkers, among them Protagoras, who is known for his wisdom and his ability to teach virtue for a price.

The central philosophical debate in the Protagoras concerns the nature of virtue—whether it can be taught and, if so, what it actually consists of. The dialogue features Socrates questioning Protagoras about his views on virtue and education, engaging in a series of intellectual challenges that ultimately aim to demonstrate the limitations and contradictions in the sophist’s position. In the process, Plato addresses significant issues regarding the nature of knowledge, education, and moral character.

The Protagoras also offers a broader philosophical inquiry into the role of rhetoric and persuasion in moral and intellectual discourse. The figure of Protagoras, who is celebrated for his persuasive ability to teach others how to succeed in public life, stands as a foil to Socrates, who seeks knowledge through dialectical questioning and the pursuit of truth.

Plot Summary of Plato’s Protagoras

The dialogue opens with Socrates encountering Hippocrates, a young man eager to learn from the sophist Protagoras. Hippocrates is enthusiastic about the possibility of gaining knowledge and virtue from Protagoras, who is well-known for his ability to teach people how to succeed in life and become effective public speakers. Socrates, however, is skeptical of Protagoras’ ability to teach virtue and wishes to investigate further whether Protagoras truly possesses the wisdom he claims.

Hippocrates, eager to follow Protagoras, brings Socrates to a gathering where Protagoras is holding a discussion. The conversation begins with Socrates’ questioning of Protagoras about whether virtue can be taught. Protagoras, in typical sophist fashion, answers affirmatively, claiming that virtue is indeed teachable. He argues that anyone who practices virtue and learns from him will be able to become virtuous in their public and private lives.

Socrates is not satisfied with this answer, and he probes deeper, challenging Protagoras to define what virtue actually is. Protagoras responds with a somewhat ambiguous definition of virtue, asserting that it is a complex combination of various qualities, such as wisdom, courage, temperance, and justice. He maintains that virtue is a form of knowledge, and thus can be taught.

Socrates, always probing for clarity, challenges Protagoras to explain how virtue can be taught if it is so complex and varied. He raises the issue of whether different virtues—such as courage and wisdom—are the same or different. Protagoras insists that the virtues are related and that teaching virtue involves cultivating all of them together. Socrates, however, presses the issue, questioning whether these virtues can truly be separated and taught individually.

At this point in the dialogue, Protagoras tells a mythological story about how Zeus gave human beings the ability to act virtuously, but also gave them the responsibility to cultivate and pass on virtue to others. This story, though entertaining, also serves as an allegory for the way in which virtue is transmitted and acquired through teaching.

Socrates, however, remains unconvinced, continuing to challenge Protagoras on whether virtue is truly teachable. The conversation turns to the question of whether people can be virtuous by nature, or whether they must learn virtue through instruction and experience. Socrates suggests that if virtue is a form of knowledge, then it would seem that those who have knowledge should naturally act virtuously, but this does not always seem to be the case. If virtue were simply a matter of knowledge, Socrates argues, then everyone who knew the right thing would always act in accordance with it.

At this point, Protagoras offers an interesting counterargument: he suggests that the problem with human nature is that people often fail to act according to what they know to be right. He claims that while virtue is knowledge, it is also a matter of habit and training. One must be taught to apply their knowledge and cultivate virtue through practice.

Socrates, in turn, criticizes Protagoras’ views by suggesting that knowledge cannot be merely a form of habit or training, for true knowledge involves the ability to act in accordance with reason. Socrates argues that knowledge must be objective, universal, and applicable to all aspects of life. He insists that virtue is not simply a matter of training but must be grounded in a deeper understanding of justice, morality, and the good.

In the second part of the dialogue, Socrates and Protagoras engage in a debate about whether virtue can be divided into distinct elements. Protagoras argues that the virtues are all related and interconnected, while Socrates suggests that the virtues must be distinct and that one must possess knowledge of each virtue individually. They discuss the possibility that one can possess some virtues without possessing others, and Socrates uses his famous elenchus (method of refutation) to demonstrate contradictions in Protagoras’ arguments. Ultimately, Socrates challenges Protagoras to show that virtue is a coherent, teachable concept, while Protagoras is unable to provide a satisfactory answer.

The dialogue ends with Socrates asserting that true virtue cannot be taught in the way that Protagoras claims, but must instead be rooted in a deeper philosophical understanding of reason and the good. However, the dialogue leaves open the question of how virtue can be acquired, and whether it is something inherent in human nature or something that must be cultivated through philosophical education.

Themes in Plato’s Protagoras

- The Teachability of Virtue

One of the central themes in Protagoras is the question of whether virtue can be taught. Protagoras, representing the views of the sophists, argues that virtue is teachable and that anyone who seeks to acquire it can do so through proper instruction. Socrates, on the other hand, challenges this view by questioning whether virtue is simply a matter of knowledge or something more complex. He argues that virtue cannot be simply taught as a skill, and that it requires a deeper understanding of human nature, reason, and the good. The dialogue explores the tension between these two positions and raises important questions about the nature of virtue and how it is acquired.

- The Nature of Knowledge and Wisdom

The dialogue also addresses the nature of knowledge and its relationship to wisdom. Protagoras views virtue as a form of knowledge, but Socrates challenges this by suggesting that true wisdom must involve understanding the essence of justice, courage, and temperance in a way that transcends mere practical knowledge. Socrates maintains that wisdom requires not only knowing what is right but also understanding the principles that guide virtuous action. This distinction highlights Plato’s larger philosophical project of defining knowledge and wisdom as more than just practical knowledge of how to succeed in the world.

Read More

- Rhetoric and Persuasion

Another key theme in Protagoras is the role of rhetoric and persuasion in shaping human behavior. Protagoras, as a sophist, emphasizes the power of speech and the ability to persuade others in the public sphere. He believes that rhetoric is a key element in teaching virtue, as it enables individuals to succeed in life and engage effectively in society. Socrates, however, is skeptical of the effectiveness of rhetoric as a means of teaching true virtue. He argues that rhetoric, while persuasive, can often be misleading and manipulative, and that true virtue requires more than just persuasive skills—it requires a deep understanding of the good and the just.

- The Role of the Philosopher

The dialogue also reflects Plato’s view of the philosopher’s role in society. Socrates presents himself as a seeker of truth who is committed to finding the essence of virtue through philosophical inquiry, rather than relying on the rhetorical and persuasive techniques of the sophists. Socrates rejects the idea that virtue can be taught in the same way as practical skills or technical knowledge. He argues that philosophy must be a search for truth, not just a tool for success in life.

- Relativism vs. Universal Truth

Protagoras is often associated with the view of relativism, the belief that moral values and truths are subjective and dependent on individual perspective. This is encapsulated in his famous assertion, “Man is the measure of all things,” suggesting that each person’s perceptions and beliefs are equally valid. Socrates challenges this relativistic view by emphasizing the need for universal standards of virtue and knowledge that apply to all people, regardless of their individual circumstances or beliefs.

Conclusion

Plato’s Protagoras is a profound exploration of the nature of virtue, knowledge, and education. Through the dialogue between Socrates and Protagoras, Plato critiques the sophistic view that virtue can be taught through rhetoric and persuasion, emphasizing the importance of philosophical wisdom and reasoned inquiry in understanding moral truths. The dialogue also examines the tension between relativism and universal truth, raising important questions about the role of the philosopher and the value of education in the pursuit of virtue.

Read More

(FAQ)

1. What is the central argument in Plato’s Protagoras?

The central argument of Protagoras is the debate about whether virtue can be taught. Protagoras, a sophist, argues that virtue is teachable through education, while Socrates questions this idea, suggesting that virtue cannot be reduced to knowledge alone and requires a deeper philosophical understanding of justice, wisdom, and the good.

2. What is the role of sophists in Plato’s Protagoras?

In Protagoras, sophists like Protagoras represent a form of teaching that emphasizes rhetoric and the practical skills necessary for success in public life. Socrates contrasts the sophists’ approach with his own, more philosophical approach to knowledge, which focuses on searching for universal truths rather than teaching individuals to succeed in a particular context.

3. How does Plato’s Protagoras explore the relationship between knowledge and virtue?

Plato uses the dialogue to challenge the idea that virtue is simply a form of knowledge. Socrates argues that knowledge alone is not sufficient for virtuous behavior, suggesting that true virtue involves a deeper understanding of moral principles, such as justice and wisdom.

4. What is the significance of rhetoric in the dialogue?

Rhetoric plays a significant role in Protagoras, as Protagoras is famous for his ability to teach persuasive speaking. Socrates, however, critiques the sophists’ use of rhetoric, arguing that it may be effective in persuading others but is not a reliable means of teaching true virtue or moral understanding.

5. Does Plato believe that virtue can be taught?

While Plato’s Socrates questions the sophists’ claim that virtue can be taught, he leaves the issue unresolved in the dialogue. However, Plato’s broader philosophical stance suggests that virtue is not simply a set of teachable skills but involves a deeper understanding of moral truths, which philosophers can help individuals pursue through reasoned inquiry.